Landowners, News Desk

- August 20, 2015

-

Views: 55

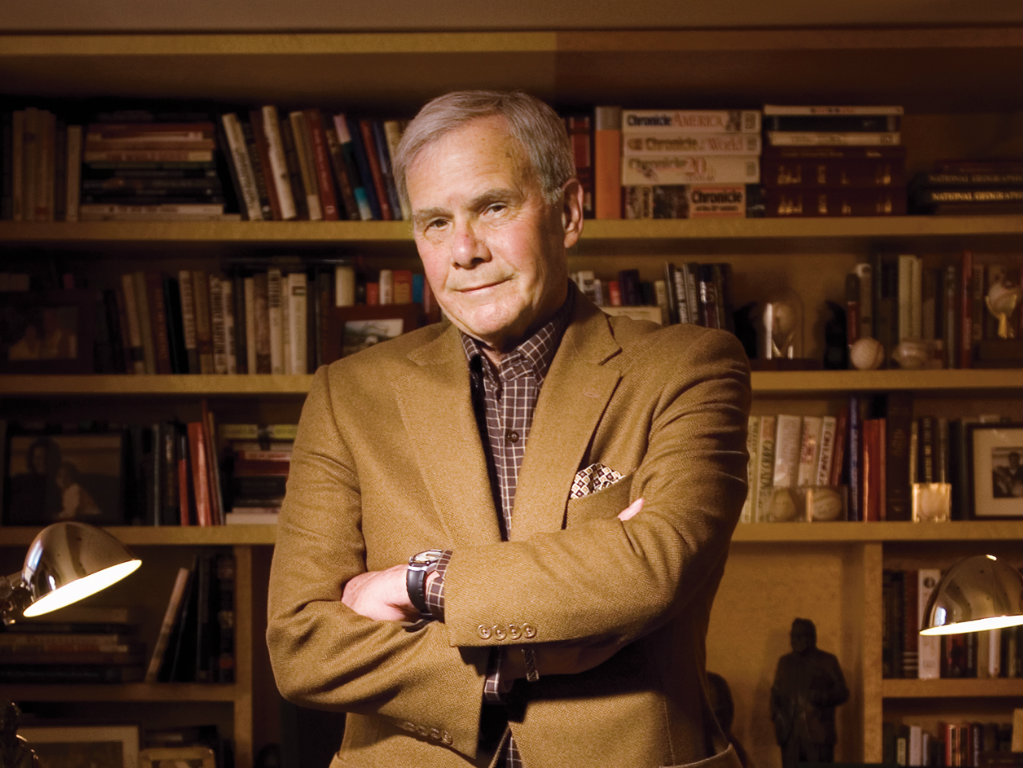

Tom Brokaw: Knowing He Has It All

Diagnosed with incurable blood cancer, one of our favorite landowners, relied on his wife of 50 years, a lot of humor, and even more gratitude.

By Laura Landro

Tom Brokaw’s authoritative reporting on such events as the fall of the Berlin Wall, the massacre at Tiananmen Square, and the 9/11 attacks made him one of America’s most trusted journalists, a broadcaster who wasn’t afraid to wear his heart on his sleeve and yet never made the story about himself.

Three years ago, though, he did become the story. Diagnosed at age 73 with multiple myeloma, a blood cancer that is treatable but incurable, he quickly fell victim to the disease’s debilitating effects, including crushing fatigue and thinning bones. He ended up with a fractured spine and lost a couple of inches in height. He was soon on a regimen of 17 drugs, barely able to walk or get himself to the bathroom. As he recounts in A Lucky Life Interrupted, it seemed as if his luck had run out.

Fortunately, it hadn’t. Thanks to his considerable financial resources, his friends in high places, and a physician-daughter, Jennifer, who acted as his advocate and adviser, Brokaw found his way to premier institutions, assembled the best doctors, and started on an aggressive course of treatment. He credits his wife of more than 50 years, Meredith, for providing the nurturing and strength he needed, and his grandchildren for providing extra motivation to beat the disease into remission.

Engaging as both a cancer memoir and a Baedeker guide through the highlights of his broadcasting careerA Lucky Life Interrupted features cameos by titans of industry, medical superstars, and assorted celebrities, many of whom pile in to offer help.

Yet Brokaw gives equal time to a brother suffering from dementia, to the injured soldiers he visits at Walter Reed Army Medical Center in Washington, D.C., and to the health-care workers he meets, who strike him, like soldiers, as mission oriented and heroic.

A recurring theme is Brokaw’s reverence for the World War II veterans he lionized in The Greatest Generation (1998). Once diagnosed and feeling his mortality, he finds himself parsing their obituaries, not for their war roles but for information about how they died and at what age. “Here’s a guy who made it to 85 and died of prostate cancer … whoops, here’s another who died at 72, his family said, of cancer-related causes.”

Brokaw knows only too well that many people don’t have his access or advantages. Thanks to his health plan from NBC’s parent company, GE, his co-pay for the powerful chemotherapy drug Revlimid, priced at more than $500 per pill and hard to get a hold of, comes to $15. “What, I thought, does a farmer in Kansas do … to get on the list and pay for [the drug], if not a breakthrough, at least a big step in the right direction?”

Despite his own near-iconic status, Brokaw has never adopted the faux patrician on-air presence of some network newsmen; he has always managed to convey gravity without pomposity. That quality is evident throughout the book, reflecting an identity rooted in one core lesson of his South Dakota upbringing: Don’t get too big for your britches. Part of Brokaw’s deep bond with Meredith is, he says, “a hardwired circuitry of Midwestern steadiness to maintain the balance.” Though he knows he is a high-profile patient, he is determined to have a low-profile demeanor.

He manages to keep his sense of humor during the darkest times, such as when he is walking up Lexington Avenue on a cold and windy day with a failing hearing-aid battery. As he tucks himself up against a falafel stand to replace it, he laughs aloud at himself.

“Here you are, Brokaw, sick with cancer, trying to learn to walk again, bedeviled by a hearing aid battery, and not even the falafel vendor cares. You’re really pathetic.”

Meeting with experts at the Mayo Clinic, where he is on the board, and at Memorial Sloan Kettering, he begins to understand the dilemmas that patients routinely face, not least what to believe when doctors give conflicting advice and how to demystify the aura that surrounds medicine. As he once told graduates at the Mayo Medical School in a commencement speech: “Most patients enter a doctor’s office or hospital as if it were a Mayan temple, representing an ancient and mysterious culture with no language in common with the visitor.”

He urges doctors to solve the communication problem and advises patients to find a personal ombudsman, a physician not directly involved in the treatment who can help them interpret a primary caregiver’s approach. He is blunt about ObamaCare, saying it is “too complicated and too wide-ranging.” He casts blame on Democrats for fumbling the structure of the plan and Republicans for not coming up with “a comprehensive bill of their own.”

Like so many patients, Brokaw finds that not all his doctors have a bedside manner; one with a particularly impressive résumé has a brusque style and little time for face-to-face consultation. What irks Brokaw most is a broader problem – the lack of coordinated care among physicians. He reminds patients to ask questions: “Am I making the progress expected? Are all the members of my treatment team working together?”

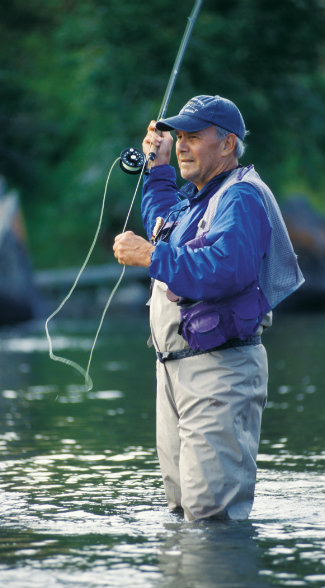

One of the worst aspects of any severe illness is the feeling of being sidelined from an active life. Brokaw laments the inability to race off to the scene of a breaking story – something he continued to do as a special correspondent after leaving the NBC anchor chair in 2004. But he mustered all his strength to get to an event he simply couldn’t miss: the 2014 commemorations in Normandy marking the 70th anniversary of D-Day.

Throughout his illness, Brokaw reminds himself to keep his life in perspective: “I wasn’t getting off a landing craft in heavy surf at dawn to face murderous fire with the odds short that I would survive 15 minutes.”

It’s the kind of insight that is typical of Brokaw’s approach to life and now to illness. Surely he will have cause to remember it again next year and for many D-Day anniversaries to come.

###

Reprinted by permission of The Wall Street Journal Copyright © 2015 Dow Jones & Company, Inc. All Rights Reserved Worldwide. License number 3632720981912.

Warning: Undefined array key 0 in /home/domains/dev.landreport.com/public/wp-content/plugins/elementor-pro/modules/dynamic-tags/acf/tags/acf-url.php on line 34

Warning: Undefined array key 1 in /home/domains/dev.landreport.com/public/wp-content/plugins/elementor-pro/modules/dynamic-tags/acf/tags/acf-url.php on line 34

RELATED ARTICLES

Land Report March 2019 Newsletter

Spring has sprung, and with it has come pricing adjustments on several legacy properties currently …

Equestrian Roundup: Florida’s Wellington

What’s the cost per acre of land in the most expensive equestrian market in the …

Sold! Connecticut’s Copper Beech Farm

Named for the large copper beech trees populating the property, Copper Beech Farm, a relic …

Elk Creek Ranch Acquires Seven Lakes

For those who are passionate about outdoor pursuits, the next great adventure can’t come soon enough.