Ranchland, Sporting Properties

- August 23, 2016

-

Views: 72

The American Landowner: Legends of Quail

Warning: Array to string conversion in /home/domains/dev.landreport.com/public/wp-content/plugins/elementor/core/dynamic-tags/manager.php on line 64

Warning: Undefined array key "separator_height" in /home/domains/dev.landreport.com/public/wp-content/plugins/jet-tricks/includes/addons/jet-unfold-widget.php on line 942

To commemorate one of the greatest years for quail, Boone Pickens invited a Who’s Who of wingshooters to his Mesa Vista Ranch.

Text by Henry Chappell | Photography by Wyman Meinzer & Russell Graves

T. Boone Pickens drives down a Mesa Vista Ranch road. He’s watching a lanky English pointer working a covey of bobwhites. The dog stops, head high, tail still flagging.

“Birds are running,” Boone says.

Sure enough, the pointer sweeps his nose back and forth, sniffing for tendrils of scent. Cold fog hangs over the prairie. Given the release command, the dog cat-walks ahead, tail whipping. Bubba Wood and Rick Pope ease along behind him. Twenty yards on, the dog points again, but before the hunters can move into position, a covey flushes and flies low over the bluestem and sage, offering no shot.

When you’re following bird dogs on the Mesa Vista Ranch, you’re hunting wild birds that know how to survive hawks, bobcats, coyotes, snakes, and the deadliest predators of all: Boone Pickens and his buddies.

A few minutes later, the dog points again, and a single bird flushes early, but not early enough. Bubba drops it and sends Katie, his little English cocker, to fetch. Rick drops a single with a tough, low, left-to-right shot.

“Starting to look a little like a bird hunt now,” Boone says.

Minutes later, another covey flushes well ahead of dogs and hunters, but the singles hold for solid points. Bubba and Rick add to their bag. Boone pulls up and rolls down his window.

“Y’all hunt way too slow,” he yells. “How do you expect to get a limit by lunchtime?”

“By not missing any birds,” Bubba shouts back. He and Boone have hunted together for decades and have taken more than a few pre-lunch limits.

By lunchtime, the hunters are delighted, and the guides disappointed. Never mind the pile of birds. On the Mesa Vista, this season’s average has been over 40 coveys per day. Somewhere amid the jovial insults, the guides check their notes and announce that the morning’s numbers are only a bit under. Now that the morning fog is burning off, conditions could well be perfect.

The night before, Boone addressed the group: “We’re having one of the best years for quail I’ve ever seen. I may never see another one like it. To celebrate, I wanted to invite the best quail hunters I know to experience the kind of hunting we have when everything comes together just right. And you-all are that group, the legends of quail hunting.”

The legends include Bubba Wood, founder of Collectors Covey, Texas’s premier sporting art gallery, member of the National Skeet Shooters Hall of Fame, and six-time member of the national All-American Team; Rick Pope, another Hall of Famer, multi-year member of the All-American Team, and chairman of Temple Fork Outfitters; Rick Snipes, Stonewall County rancher, founding member of the Rolling Plains Quail Research Ranch, fanatical quail hunter, dog man, and conservationist; Joe Crafton, cofounder of Park Cities Quail, which has raised $6 million for quail conservation, and the new owner of Collectors Covey; Pete Delkus, chief meteorologist with WFAA-TV in Dallas and another serious hunter and conservationist; and John Thames, publisher of Covey Rise. To document the day, Land Report editor Eric O’Keefe invited Wyman Meinzer and Russell Graves to bring their camera gear. I got to watch and pet a lot of bird dogs – excellent work when you can get it.

In 1971, when Boone bought the first piece of what is now the Mesa Vista, it was, in his own estimation, “so poor the jackrabbits were carrying their lunches.” Heavy grazing had reduced the rangeland to sparse grass and bare ground. During wet years, when it might have partially recovered, previous owners punished it by stocking more cattle. Depending on rainfall, the quail population swung between boom and bust. It consisted of roughly 90 percent blue (scaled) quail – a hard-running species associated with arid grassland – and 10 percent bobwhites.

Having hunted in South Texas and all over the Rolling Plains, Boone sensed that the rolling sand hills and bottoms south of the Canadian River had all the makings of great quail country. Yes, the Northern Panhandle suffers occasional hard freezes. But supplemental feeding could increase survival. Cool fall and winter days are far more comfortable for hunters and dogs than the sweltering South Texas heat. Furthermore, by midseason, hunters and guides could devote their full attention to shooting and dog work instead of watching for rattlesnakes.

As his acreage increased and cattle leases expired, Boone realized that his passion lay in wildlife habitat, not ranching. The few cattle that grazed on the Mesa Vista were strictly management tools, agents of disturbance consistent with Aldo Leopold’s tool kit: “The ax, the plow, the match, and the cow.”

Boone soon added another resource: The Oklahoma State geologist began to drill water wells. Although he knew his land sat on the Ogallala Aquifer, “the well-spring of the High Plains,” the easy abundance and quality of the water surprised him. “We knew right away that we were in the fat,” he tells me.

Having long observed that creek bottoms provide the most consistent hunting, he wondered if man-made creeks might provide better habitat. Here, as he’s often done, Boone bucked convention. Quail don’t require surface water. They extract water from food. Yet quail chicks require an abundance of protein-rich insects to survive those precarious first few weeks prior to fledging. Boone reasoned that since quail chicks require insects, and insects require moisture, new creeks might provide a hedge against drought. Today, some 25 miles of buried drip line creates pools at thousand-foot intervals, ensuring abundant moisture even during dry years. Although some professional wildlife managers remain skeptical, those who’ve hunted at the Mesa Vista agree that the drip lines attract quail and other wildlife. Furthermore, during droughty spells, coveys are larger and more abundant along Boone’s creeks than in good habitat elsewhere.

Boone also relies on more than a thousand feeders to supplement the abundant natural food supply. During rough winter stretches, when birds might be too weak to scratch through ice or snow to reach ragweed, sunflower, or croton seeds, the nutritious supplement enhances survival. Biologists worry that feeding concentrates birds, which in turn attracts predators. Research supports those fears. To minimize predation, feeders are placed inconspicuously just inside patches of woody cover that provide overhead protection from avian predators and screening protection from terrestrial predators like raccoons and bobcats. Threatened birds can flush or run into nearly endless cover.

Boone no longer frets about professional opinions. He simply points to the results, which Bubba sums up neatly: “There’s no question that Boone’s feeding and water program makes a huge difference. Mesa Vista beats anyplace I’ve ever hunted.”

Most important, Boone has given the mixed prairie at the Mesa Vista time to heal. Prior to settlement in the late nineteenth century, the grasslands of the Texas Panhandle saw only periodic disturbance from nomadic bison herds, wildfire, and searing drought – all of which set back plant succession and facilitated long periods of natural regeneration. When summertime air temperature reaches 100 degrees, ground temperatures can hit 120 degrees. Without the life-saving shade provided by native grasses, successful nesting is impossible.

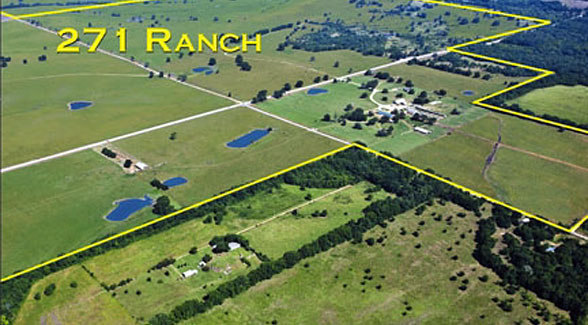

Over the years, Boone acquired adjacent parcels. Unlike cattlemen, who tend to acquire neat blocks of land, Boone focused on creek drainages, which feature the most valuable wildlife habitat. Today, Mesa Vista Ranch, with the Canadian River along its northern boundary, covers some 65,000 acres, all in Roberts County. What started out as a small patch of overgrazed pasture has grown into a renowned hunting ranch, complete with a world-class lodge capable of hosting dozens of guests in numerous structures, a 12,000-square-foot lake house, and dozens of other amenities – some manicured, others rustic.

“I suspect that after this last drought, Mesa Vista Ranch naturally restocked most of Roberts County’s quail population,” Bubba says.

Rick Snipes adds, “What’s unique about Boone’s ranch is that it’s here for the quail. Period. Not cattle. Not cattle and quail. Quail. The first question Boone asks before anything is done on the ranch is, ‘How will it affect our quail?’”

Thanks to much improved cover, the quail now run about 90 percent bobwhite and 10 percent blue quail – a complete reversal of the hardscrabble 1970s ratio.

After lunch, I pile into the back seat of a hunting truck with Rick Pope and Joe Crafton. Our guides, ranch manager Keith Boone and Ryan Hunter, promise to make up for the morning’s light shooting. The truck kennel houses a few pointing dogs, a couple Labs, a cagey springer spaniel, and Joe Crafton’s excellent young Lab, Lucy.

Boone and Keith have refined the Mesa Vista hunting system to maximize efficiency and flexibility. Three hunting rigs carry guides, hunters, water, and equipment afield. Each rig – a one-ton, four-wheel-drive pickup with a Jones dog box – can hold as many as ten dogs. Keith usually runs two pointers at a time and puts down a fresh brace every 20 minutes or so. Frequent rotation ensures snappy dog work and minimizes mistakes. Labs and spaniels stay on the truck or at heel until sent to retrieve.

Keith eases the truck down ranch roads, checking promising cover. He or Ryan often spot coveys loafing near the road, usually in the vicinity of a feeder. Out come dogs and hunters. The fact that I saw very few staunch points near the feeders should dispel any notions about this being a “turkey shoot.” In nearly every case, the birds run, then flush wild. The real dog work and display of shooting ability begins once singles spread about. Keith does the dog handling while Ryan stands atop the truck to mark the singles. Both guides wear radio headsets. Whenever Keith requests extra dog power, Ryan jumps down and unlatches a kennel door. The requested dog blasts off after the crew.

Although the pointing dogs are natural big runners out of famous field trial and shooting dog lines, they work closely and handle nicely to Keith’s whistle and hand signals. Retrievers, spaniels, and pointing dogs stay out of each other’s way even when the shooting gets hot, with several singles flushing at once and multiple dogs retrieving.

The system allows Joe to stride out after the dogs and school his new pup, Lucy. On the other hand, Rick Pope, still recovering from a rattlesnake bite, limps along on a sore ankle. After a quick double or two at each stop, he’s happy to be picked up and driven down the road a few hundred yards to meet the rest of the crew.

Over the next three hours, the team moves at least 20 coveys. Limits are reached in short order, and the dogs get into plenty of birds – much to the benefit of young Lucy and the satisfaction of her master. Speculation about the success of the other two trucks foreshadows much jawing and good-natured harassment over cocktails at the lodge. Over the years, the Mesa Vista kennel has grown to fit Boone Pickens’s ambitions and hospitality. The immaculate facility houses around 25 pointing dogs, a couple spaniels, and 13 Labrador retrievers. The ranch hosts 50 to 60 hunts per year. At times, all three trucks are out at once, so any dog that makes the Mesa Vista team will work thousands of quail over an eight- to ten-year career. Mesa Vista retrievers and spaniels retrieve more downed birds in a couple seasons than most gun dogs retrieve in a lifetime. Nowadays, most Mesa Vista pointing dogs are English pointers out of Miller’s Chief and Guardrail lines, but Keith keeps an eye out for talent wherever it might be found. He also keeps a few English setters and, recently, a big-running German shorthair that Boone likes. Most of the Labs are homegrown.

On the final morning, we head for the center pivot irrigators, around which 250 pheasants had been released into a cover mix of sorghum, redtop, foxtail millet, and haygrazer. It was show time for the Labs and spaniels that work ahead of the line of hunters and guides. Notorious runners, pheasants rarely hold for pointing dogs. Although there is a small breeding population on the ranch, most of the pheasants are released. However, unlike pen-reared bobwhites, flight-conditioned pheasants quickly acclimate to excellent habitat and can be nearly as challenging as wild birds.

Over the next hour, I witness a display of shotgunning skill and dog work that I’m likely never to see again. The birds flush and fly hard in a stiff wind, often well ahead of the hunters. The dogs stay busy fetching birds and sorting out runners and cripples. At the end of the shoot, John Thames, looking a tad dazed, shakes his head and mutters, “I’ve never seen anything like it.”

Mesa Vista Ranch reflects Boone Pickens’ lifelong commitment to conservation. His devotion to bobwhite quail and the Texas quail hunting tradition continues to shape this unique place, and to contribute to our body of wildlife management knowledge.

Bubba Wood describes his longtime friend succinctly: “Boone isn’t a rich guy who hunts quail. He’s a quail hunter who became a rich guy. Believe me, there’s a big difference.”

RELATED ARTICLES

Housing Rebound Revives Timber Industry

A depleted housing supply coupled with resurgent consumer demand has brought economic vitality to US …

Sold! Oregon's 42,500-Acre Ochoco Ranch

The heavily timbered Ochoco Ranch, located in Central Oregon just 30 minutes from the red hot market in …

Louis Bacon Adds Historic Orton Plantation to Landholdings

A successful hedge fund manager and dedicated conservationist, Bacon’s 202,000 acres earned him No. 40 …

Elk Creek Ranch Acquires Seven Lakes

For those who are passionate about outdoor pursuits, the next great adventure can’t come soon enough.