A landmark mitigation project in South Carolina is built on cooperation and conservation.

By Corinne Garcia

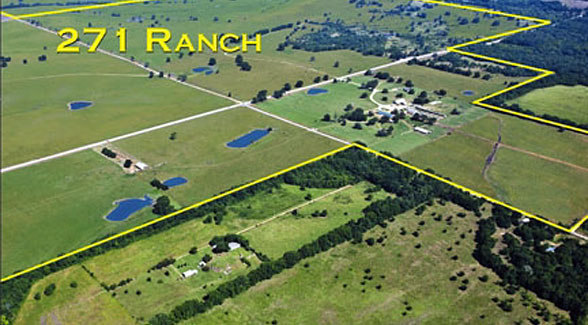

In May 2008, when American Timberlands CEO Tom Rowland first set foot on Gunter’s Island – a lush 6,859-acre holding with more than 10 miles of frontage on South Carolina’s Little Pee Dee River – he immediately knew that the canopied acreage was a standout tract.

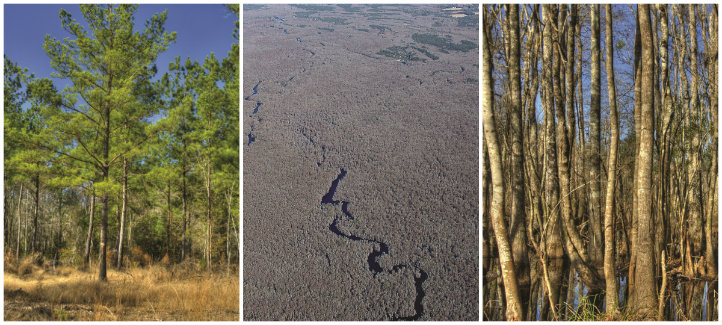

“Gunter’s Island has 10 miles of contiguous, second-generation bottomland hardwood adjoining sugar sand ridges, which is a big deal ecologically,” he says. “In addition, its exceptional habitat is home to healthy populations of black bear, white-tailed deer, wild turkey, wild hog, duck, dove, and a plethora of other things.”

“My thinking was that it would be a great state park, and I commented as such to the team. Little did we know that we would end up doing what we did,” Rowland says.

What American Timberlands has done in the decade since is collaborate with a key group of federal and state agencies. The end result? A landmark mitigation deal, one that required the right project, the right land, and the right mix of people dedicated to pursuing the best interests of economic progress, the environment, and the people of South Carolina.

American Timberlands bought Gunter’s Island in 2008 with an Atlanta-based real estate private equity fund as part of a package deal in Horry County. Thanks to 10 miles of Little Pee Dee River frontage and an intact Carolina bay, it was clear from the outset that there was potential for a mitigation project, but not in the traditional sense.

Land Lesson No.1 | MITIGATION BANK

A conserved tract of land that offers credits to entities that need to offset adverse impacts of a bridge or a shopping center.

A traditional mitigation bank model would mean the restoration and preservation of Gunter’s Island’s riparian areas in exchange for credits that could be sold, much like the company did with the Carter Stilley project, the 1,304-acre mitigation bank that American Timberlands created not far from Gunter’s Island. (See The Land Report, Fall 2016). Upon approval by the US Army Corps of Engineers, such credits could then be marketed to developers or other entities that needed to offset adverse wetland impacts that their projects incurred.

Due to its size (more than 10 square miles) and the significance of the natural resources on Gunter’s Island, American Timberlands chose to explore a different route, one called permittee-responsible mitigation.

“When you think about traditional wetland mitigation, it involves selling credits to folks like the state department of transportation and real estate developers that are impacting wetlands,” says Rowland. “By comparison, with a large-scale impact, like a factory or airport, it makes more sense to do a single project of equal scope rather than traditional banking. In this case of Interstate 73, it was the preservation of Gunter’s Island.”

“The idea is, ‘OK. We are going to have 300-something acres of wetland impacts. Why don’t we find a piece of ecologically significant land and use that to mitigate the impacts?’” Rowland says. With this in mind, he and his team at American Timberlands set out in search of the right partner for Gunter’s Island, one with an oversized mitigation need.

On large-scale projects, it’s not uncommon for American Timberlands to reach out to federal and state agencies (or vice versa) that are involved in substantial projects. In this instance, the timing could not have been better.

“For over 10 years, we worked on the design and permitting for Interstate 73, between Rockingham, North Carolina, and Myrtle Beach, South Carolina,” says Bob Perry, the former Director of the South Carolina Department of Natural Resources (DNR) Environmental Affairs.

“It was a very extensive, lengthy, and very complete process for determining the environmental impacts associated with building the roadway. In order to get the permit, the South Carolina DOT would have to meet the mitigation,” Perry says.

LAND LESSON No.2 | PERMITTEE-RESPONSIBLE MITIGATION

A single tract of land that is used to offset the adverse impact of a major development, such as a highway or an airport.

Perry’s department, Environmental Affairs, assists regulators with the science side of the permitting process. “When we were in the early stages [of permitting Interstate 73], all agencies were in agreement that the project would require a substantial mitigation package to offset the impacts, which were many,” Perry says. “You can imagine it took a long time to find the right opportunity.”

While vetting possible mitigation packages, Perry and his colleagues met with numerous organizations, including government agencies, land trusts, and companies such as American Timberlands. At his initial meeting with Perry, Rowland proposed Gunter’s Island as a possible solution set for the I-73 extension.

“By itself, Gunter’s Island is a meaningful piece of property,” says Lorianne Riggin, who recently succeeded Perry as director of Environmental Affairs. Riggin also worked on the Gunter’s Island project from day one. “It has the location on Little Pee Dee, an outstanding resource water, sundry different wild species that use the habitat, and such a large riparian zone to improve hydraulics and provide area for the natural resources to thrive.”

The project then moved on to the South Carolina Department of Transportation (DOT), where it landed on the desk of the commission chair, Mike Wooten. “My goal was to get the permit process finished for I-73 in South Carolina, and I had been personally working towards this goal for 27 years,” Wooten says. He looked at both mitigation models, the traditional credit-based bank and the permittee-responsible mitigation.

“I couldn’t authorize spending that amount of money without weighing each route against the other,” he says. Although both cost about the same, traditional mitigation credits can take three to five years to market. Permittee-responsible mitigation is effective immediately. Then, of course, there was the prospect of turning over such a fine piece of land to the people of South Carolina.

All of the collaborators breathed a huge sigh of relief when the Corps of Engineers approved the permitting of the Gunter’s Island Mitigation Plan in June 2017. Two months later, South Carolina DOT closed on Gunter’s Island for $18.3 million and began the extensive preparations necessary to turn it over to DNR’s Heritage Trust program.

“It’s a great success story,” Wooten says. “The guys from American Timberlands were very helpful, and we were very fortunate to have deal makers throughout instead of deal breakers. Life is about relationships, and we happened to have the right people doing the right things at the right time.”

“These kinds of deals require a tremendous amount of collaboration and trust between different agencies,” adds Riggin. “We are well known in South Carolina for being able to pull these kinds of deals off, which speaks well of the ability to collaborate productively to get things done so the people benefit and the wildlife benefits.”

Gunter’s Island will soon open to the public. “We’ll make sure the roads are safe, signage is put up, do a dedication, and then provide the public access,” Riggin says. The island will offer hiking, hunting, fishing, and more.

Although Interstate 73 is still a long way from completion, a significant hurdle has been cleared. “South Carolina needs I-73. It is essential for continued economic development and the safety our citizens,” Rowland says. “It will promote tourism, facilitate traffic flow, and provide an evacuation route from hurricanes. It’s vital to Myrtle Beach.”

For American Timberlands and its partners, this process started with boots on the ground and an insightful first look at a piece of land.

Says Rowland, “One of the things we do in due diligence is think about who the next owner of a piece of property will be. From the very beginning, we recognized that this was an asset that needed to belong to the state and the citizens of the state. What we did here is find the nexus between economic development and environmental stewardship.”