Not all public lands are created equal. That is especially the case out West where almost half the land – 47 percent – is owned by Uncle Sam.

Text by Ken Mirr

Four or five years ago, I listed a historic ranch in Utah right next to Capitol Reef National Park. In operation for more than a century, the Sandy Ranch is a high-desert outfit that runs about 1,000 head on 6,970 acres. Doesn’t make sense, does it? A cow-calf pair per every seven acres in the middle of the desert?

Welcome to the West.

The reason these figures do make sense is because immediately adjacent to the Sandy are more than 170,000 acres of Bureau of Land Management lands that the ranch leases. And in the Dixie National Forest, the ranch leases 72,000 acres of grazing lands. There’s a lesson here. Landowners and their managers must understand the underlying advantages and the potential conflicts to owning land in the West.

The overwhelming majority of the federal government’s 610 million acres falls under the jurisdiction of four agencies: the Bureau of Land Management (BLM), the National Park Service, the US Fish and Wildlife Service, and the US Forest Service. The Interior Department oversees the first three agencies; the Forest Service is under the Department of Agriculture. Each of these federal agencies has its own rules and procedures about access to and use of its lands.

In my experience, the most common interface ranchers have with federal public lands is via the BLM and the Forest Service. The Park Service runs a distant third, and Fish and Wildlife fourth. While Fish and Wildlife administers 89 million acres of federal land, only a small portion can be found in the West; 86 percent of Fish and Wildlife lands are in Alaska. Additional holdings are along the Gulf Coast.

By contrast, the BLM manages more land – over 248 million surface acres – than any other federal agency. The agency also manages the mineral estate on 700 million subsurface acres. The latter figure tallies out to 30 percent of the nation’s minerals. BLM management priorities are similar to those of the Forest Service. They include grazing, timber, energy development, recreation, wildlife and fish habitat, conservation, and watershed enhancement. Historically, each agency has emphasized different uses with BLM managing more rangelands and the Forest Service more forests.

More than 155 million acres of BLM land is used for livestock grazing. That works out to nearly 18,000 permits and leases held by ranchers who primarily graze cattle and sheep. Permits and leases generally cover a 10-year period and are renewable if the terms and conditions of the expiring permit are being met.

Keep in mind that the history of the Western states is closely tied to livestock grazing. During the 1800s, large ranching operations were established using the free forage typically available on public domain lands. While these cattle and sheep empires waned after restrictions on grazing were imposed in the early 20th century, much of the culture of the rural West is still closely tied to this heritage. Many rural communities are still dependent upon ranching for their economic livelihood, and most ranches out West utilize federal and state lands for at least a portion of their grazing lands.

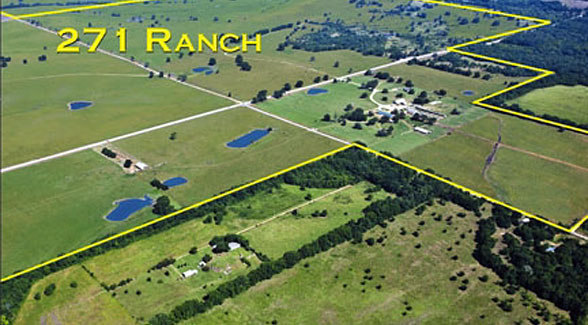

One of my current listings, the Lower Ranch at Cross Mountain (above), exemplifies this. The ranch’s 27,000 deeded acres are not contiguous. Thanks to BLM leases, these private lands are stitched together with more than 100,000 acres of BLM land, filling in the gaps and creating a unified management opportunity.

The Forest Service is the oldest of the four federal land management agencies. Its mission is to sustain the health, diversity, and productivity of the nation’s forests and grasslands to meet the needs of present and future generations. Currently, the Forest Service manages approximately 193 million acres of federal lands. Not only do these forests contain some of the most breathtaking scenery in the country, but they also possess valuable resources. And they are the source of drinking water for millions of Americans.

Forest Service lands are managed for multiple uses, including timber, water, recreation, conservation, livestock grazing, wildlife and fish habitat, and wilderness. Landowners interface with the Forest Service on a myriad of issues. For instance, ranchers typically have to deal with grazing rules and regulations that bear some similarity with the BLM.

A private landholding that shares a fence line with a national forest enjoys many benefits ranging from scenic vistas to wide open spaces. Privacy, however, is not always guaranteed. Last year, the Forest Service welcomed an estimated 177 million visitors to our 154 national forests. These visitors hiked on 158,000 miles of trails and drove every imaginable vehicle on approximately 375,000 miles of forest roads.

Another area of concern is wildfires jumping from public to private lands. According to the Colorado State Forest Service, one-fifth of that state’s forestland succumbed to the mountain pine beetle. The devastating loss of 800 million trees on 3.4 million acres has a wide range of implications, including a dramatic shift in budgetary allocations by the US Forest Service. Fire suppression once took up 15 percent of the agency’s budget. That amount has ballooned to 55 percent.

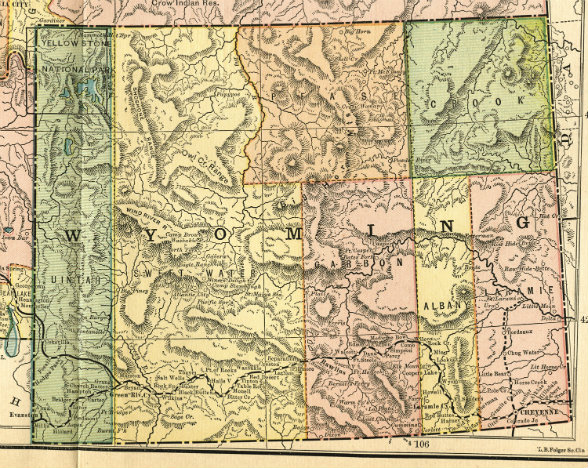

Believe it or not, there is a lot more to the National Park Service than national parks. The agency also oversees national monuments, battlefields, lakeshores, seashores, recreation areas, scenic rivers and trails, and other areas. At all these areas, the National Park Service is highly vested in preservation. (Compare this to the Bureau of Land Management and Forest Service lands, which have multiple use mandates.) Approximately 84 million acres fall under its authority; roughly one-quarter of that acreage is out West, including Yellowstone National Park, the world’s first national park. With more than 4 million visitors in 2017, Yellowstone is one of the nation’s most popular parks. It has also seen its share of controversies, including one that pit neighboring landowners against the park service’s decision to reintroduce the grey wolf into the Greater Yellowstone ecosystem in 1995.

My experience working with landowners who neighbor a national park has generally been positive. Take, for instance, Utah’s Trees Ranch which I listed in 2011. One of the most scenic properties in the Southwest, the Trees Ranch borders Zion National Park. With 4.5 million visitors a year, Zion enjoys greater visitation than Yellowstone. Privacy issues immediately come to mind, right? Wrong! For starters, Lower Parunuweap Canyon has been designated a natural research area. This means that the acreage on Zion closest to the ranch is off limits to the public. Secondly, additional parkland adjoining the ranch has been designated “wilderness.” Thirdly, federal legislation has designated the adjoining stretches of the East Fork of the Virgin River and Shunes Creek as wild and scenic. Rather than impact the ranch negatively, proximity to this popular national park has imparted additional privacy.

In a curious incident of statehood, most states west of the Mississippi River received grants of federal land to assist in the funding of public education and other programs. Known variously as school lands, trust lands, or grant lands, these properties are managed by agencies called land offices, land commissions, or land boards.

There are approximately 46 million acres of state trust lands nationwide. The lion’s share – more than 40 million acres or approximately 85 percent of this total –is concentrated in nine Western states: Arizona, Colorado, Idaho, Montana, New Mexico, Oregon, Utah, Washington, and Wyoming.

Because of state trust lands’ provenance, the public does not necessarily enjoy access to these lands for recreational uses as they do BLM, national forests, or national parks. Instead, they benefit the public by the revenues they generate.

The management of state trust lands focuses primarily on generating revenues via livestock grazing and the lease and sale of natural resources such as timber, coal, and oil and gas. The rules and regulations applicable to state trust lands have changed significantly over the years and can vary not only from state to state but also with the different federal land management agencies. The good news is that these permits tend to have many similarities with the BLM’s.

Prior to founding Mirr Ranch Group, Ken Mirr worked as a public lands attorney and assisted ranchers, ski areas, natural resource companies, conservation groups, and others with transactions involving federal and state land agencies. The Denver-based broker won 2015 Ranchland Deal of the Year honors for the sale of Colorado’s JE Canyon Ranch.