A centuries-old fracas involving a caustic boundary

dispute shows no signs of abating.

By Eric O’Keefe

One of the country’s most contentious water wars has reached a boil, and there’s a high probability that a conclusive decision will only emerge courtesy of the highest court in the land. But first — the bizarre backstory.

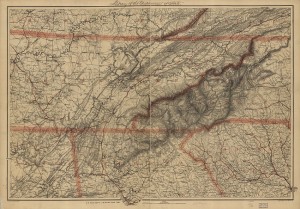

Almost two centuries have passed since Tennessee and Georgia commissioned a survey to plot their shared boundary. As stipulated by Congress, the states meet at the 35th parallel. Unfortunately, the mathematicians who oversaw the survey – Messrs. James Camack and James Gaines – were a tad askew in their final calculations. (This happened more often than one would expect.) Per the Camack-Gaines survey, which Tennessee signed off on centuries ago and Georgia disputes to this day, the Tennessee-Georgia state line runs a mile or so south of the 35th parallel through Dade County, Georgia.

This innocuous blunder has colossal implications. The disputed territory – some 43,000 acres that some refer to as Occupied Georgia – has long been designated as part of Tennessee. The most critical portions include a tiny sliver that borders the mighty Tennessee River. Because of this gaffe, Georgia has no Tennessee River frontage, a condition that is especially critical for Atlanta. As one of the fastest-growing metropolitan areas in the nation, Atlanta depends on the Chattahoochee River. Unfortunately, the Chattahoochee has the unenviable distinction of being the smallest river to serve as a primary water source for a major city in the U.S. To make matters worse, the Peach State was more than parched last year. It was scorched. The USDA classified 98 percent of Georgia as abnormally dry to having extreme drought conditions.

So what are Georgia’s options? First and foremost, it needs to continue to raise a ruckus. The rationale behind this strategy involves a legal concept known as acquiescence. Acquiescence is one of those times when silence is not golden. Essentially, failure by Georgia to object to a perceived infringement of its rights could subsequently disqualify it from making a claim in a court of law. Hence, a voluminous paper trail that dates back to 1818.

Georgia’s elected officials are definitely taking a proactive approach. Earlier this year, both houses of the Georgia legislature passed a resolution calling for a correction of this centuries-old survey. If no agreement can be reached with Georgia’s Volunteer neighbors within a year, the resolution directs Sam Olens, Georgia’s Attorney General, to commence litigation. This is where things get ugly, because Georgia won’t be seeking just the 1,000 or so acres in Marion County that would facilitate access to the Tennessee River. It directs Olens to sue for the entire area south of the 35th parallel: more than 68 square miles, several townships, as well as substantial Tennessee River frontage.

Students of the Constitution know that only one court can hear disputes between states: the U.S. Supreme Court. In such a setting, the Supreme Court would appoint a special master who would gather all the facts and make a recommendation. This process would require three to five years – considerably less time than a case starting in federal district courts, and the decision cannot be appealed.

One final note. The amount of water that Georgia seeks to withdraw from the Tennessee? It turns out that it is actually less than what it contributes. According to some estimates, approximately 7 percent of the flow of the Tennessee – an estimated 1.6 billion gallons a day – originates in Georgia via the Toccoa and Nottely Rivers. Georgia seeks to divert less than 500 million gallons.

For an excellent briefing on the history and paper trail of this dispute, Google “Tapping the Tennessee River at Georgia’s Northwest Corner: A Solution to Georgia’s Water Supply Crisis.” Prepared by William Bradley Carver and Dargan “Scott” Cole Sr. at the Atlanta law firm of Hall Booth Smith, the paper was presented at the 2011 Georgia Water Resources Conference in Athens, Georgia.