He has a front-row seat at some of the most momentous events in recent history, yet to hear him tell it, what happened on a river bank on his Montana ranch a couple of years ago could well be just as unforgettable.

By Eric O’Keefe. Photography by Tom Murphy (fishing) and Sean McCormick (portrait).

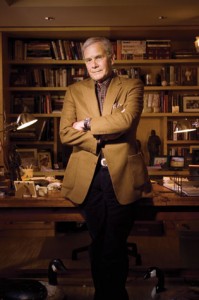

For decades, millions of Americans tuned in to Tom Brokaw when they wanted answers. So much so that when the NBC anchorman stepped down in 2004, the Peacock Network wisely offered him a 10-year contract extension to produce documentaries and sit in on major events. In an age of media midgets, this is one guy who didn’t need to be on the market.

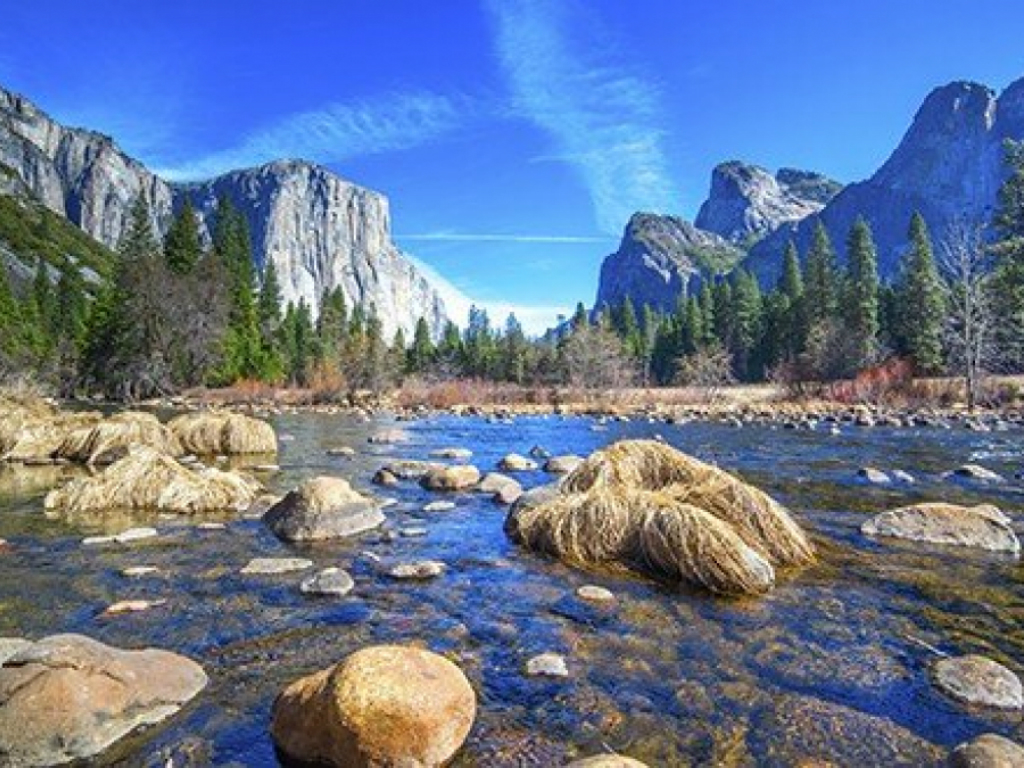

But Brokaw is also a gifted storyteller, a fact well known to anyone who has read The Greatest Generation or his autobiography, A Long Way From Home. This facility quickly becomes evident one afternoon at his NBC office overlooking Rockefeller Center. The conversation had shifted from dates and places to the Tom Brokaw America doesn’t see on TV, the man who emerges when he arrives in Montana and sets foot on his ranch. Brokaw starts off by describing how much he loves to go out by himself. “I think the wilderness is at best a solitary experience,” he says, then quickly cuts to the chase: “I’ll tell you one quick story. This is, for me, the apotheosis of the Montana experience.

“Two years ago in the early spring, I was out by myself on our property. And I was on a ridge overlooking a bend in the river, and a herd of mother elk came out with their newborn calves. The calves couldn’t have been more than three weeks old. River’s running very high. They took a long look at me. I’m 150 yards away. I stood stock still. The mothers led the calves into the high river. Most of them made it. They had to kind of crash their way through the hawthorn bushes on the other side. One did not. It got swept downstream. Made its way onto an eddy, got back on the sandbar, tried a second time, missed a second time, missed a third time. Now it’s pretty tired. Goes up and stands on the sandbar, and it just looks painfully at its mother across the way. Honest to God, this cow elk looked at that calf and nodded, waded back into the river, nuzzled the calf, led it upstream to a safer part of the river and across the river where the rest of the herd of mothers and their offspring were waiting, and then they disappeared over the hill.

“I challenge you to duplicate that anywhere else in American life. It was just the most rewarding kind of experience. It’s truly spiritual in its own way, and I keep that memory with me with a lot of others,” he says.

Brokaw’s enthusiasm for this other life of his masks a key fact: Montana wasn’t even on his radar screen until he was almost 50. Although he grew up next door in South Dakota–his family had homesteaded in the Dakota Territory in the late 1800s–his career as a journalist took him every place but the American West. He started at KMTV in Omaha, anchored the late evening news on WSB-TV in Atlanta, and then joined KNBC-TV in Los Angeles. He got tapped for the big leagues in 1966 when NBC News hired him, and with the exception of a stint as the network’s White House correspondence in the 1970s, he’s been working in New York City, anchoring the Today show from 1976 to 1981 and the Nightly News from 1982 to 2004.

So how did he first make his way to Montana? On assignment of course. “I was drawn to Montana originally because I went out there to shoot a documentary, and also I was invited to the Montana Bar Association to give a speech,” he says. “The fee that I came up with was they had to drop me at a trail head and pick me up five days later. My wife and I were pretty avid backpackers at the time. And we’d not been in Montana before that. We were thunderstruck frankly by the amount of space that was there–not just the national parks, which we were familiar with, but the wilderness areas and other places.”

What got him back a second time? Another assignment.

“I shot a documentary in a small town called Absarokee down in Stillwater County about the disappearing family ranch … and it became more of an organic relationship at that point,” he says.

Point of fact: When anyone with substantial media experience describes a relationship as “organic,” a major acquisition is imminent. In Tom and Meredith Brokaw’s case, it was time to buy a ranch.

“I didn’t know what that meant frankly. It was kind of a romantic idea that I had of buying a piece of ground. I was really looking for 100 acres and a river, and that’s the hardest single thing to find. And I kept at it, kept at it, kept at it. My wife never believed it would come to fruition. And it did. And it was a life-changing experience for the whole family,” he says.

Oddly enough, the property they now own didn’t fare that well in the initial judging. “The first time I looked at the ranch that we now own, it didn’t take. And I’ve often wondered why. I was at the end of a long day. I was tired. We’d been fishing, pretty hot,” he says.

The second go, however, was a charm. “I went back and rode the property with the then owner and saw all the dimensions of it and fell in love with it,” he says. The next step was to convince his wife.

“I got two partners because my wife was so resistant to the idea,” Brokaw admits. “I didn’t want to step off the cliff on my own and paralyze me. So I had two partners at the time, and we bought it. And it took my wife six months to come out, and then she fell in love with it. And now we own it entirely.”

The land itself is just over a mile high. Crow Indians once used it as a summer hunting ground. A Norwegian immigrant homesteaded the property in the early 1900s. In 1989, the New York broadcaster began journeying west with his family. At first it was for a week at a time. Then two. Last summer the Brokaws spent four months on their West Bolder Ranch.

Brokaw describes his experience as a landowner as an evolution. “We tried everything,” he says. “We took the fences down where we didn’t like them. We fenced off the riparian zone because we wanted to bring that back. The cattle were allowed to graze right down to the river. We had a leafy spurge problem that we didn’t know what that meant. Then we found ways of trying to deal with that. Putting sheep on and getting biologicals, and it got to be interesting. With every passing year we came to know more about what we were involved in and what was required. I’m to the point now where I think that we’ve been good stewards of the land. We’ve worked hard at it. Getting the leafy spurge down. Keeping the grasses down.

“We run bison on about half the ranch. On the other half, we lease to a local cowboy who … has a mother-calf operation. It’s good for that part of the land where he grazes his cows because it keeps the grass down. We had fires last year that, I think to a lot of outsiders, were pretty destructive. To us they were renewing. They burnt primarily our grassland, although some timber as well. But I’m relieved. Nobody got hurt. No structures were burned, and it’s going to be good for the ground.”

After almost two decades on his property, Brokaw is anything but a passive landowner. The pace of his voice quickens as he describes the challenges the land affords, the biological puzzles, and the sort of problem solving that has stimulated as well as preoccupied Montana landowners for generations.

At times there was a bit of a learning curve. “One of the big mistakes is that we tried to run cows for a while on our own and have a cow-calf operation. It was too high, too wet, too cold to calf. We were doing it, in part, for the managers that we had at the time–a couple that wanted to make some extra money and loved doing it. And it just wore them down and wore us out as well. So that was a mistake,” he says.

One of his prouder accomplishments is a project that was undertaken in conjunction with a neighbor to increase the upland bird population. “We put in two acres of milo down along the wetlands just so that they would have some feed. And we’ve allowed grasses to grow higher in some of the ravines,“ he says.

Such stewardship has paid big dividends. “We’re going to work harder at it now because we’ve learned that if you do just a few things the right way, the bird population goes way up. It’s Hungarian partridge and sharp-tailed grouse but also rough grouse and other things.”

“Tom is a student, an inquisitive fellow,” says renowned horseman Buck Brannaman, who takes my call at his Wyoming home. Brannaman knows the county in and around West Boulder Ranch. He served as a technical advisor on the set of The Horse Whisperer, which was filmed not far from the property. Brannaman met Meredith Brokaw not long after the couple closed on the ranch in 1989. He was giving one of his many annual clinics, and she attended. She so enjoyed his approach to horsemanship that she invited him to conduct a private clinic at the family’s ranch. Brannaman has been a regular every summer since.

“It’s kind of a tradition,” Brannaman says. “The clinic is usually four days. Tom and Meredith keep it small. They always invite about 10 of their family and friends. It’s a family get-together for them–they’ve got a great family–and it’s become a real social thing for us. We do a little fly-fishing. We always have dinner on the Fourth of July at Mike Keaton’s place [the actor owns property nearby]. And then we go back to the Brokaws‘. Every year Tom sets off fireworks on the bridge. I think he’s a pyromaniac at heart.”

Newcomers are always subject to scrutiny, especially in Montana, a state whose incomparable beauty has been attracting well-heeled buyers from both coasts for decades.

“Frankly, there is always going to be a certain element among the locals that are not going to understand Tom,” Brannaman says. “He’s too famous. He couldn’t possibly be like-minded. But I couldn’t disagree more. Tom is very astute. Very open-minded. Ask him about his ranch 10 years from now, and I promise you what he’ll tell you will be different then from what he’ll tell you today. Each piece of property is different. Tom knows that. He knows that you have to learn your ranch. That’s kind of the fun stuff.”

When it comes to fitting in, Brokaw knows his place, and he knows it for the right reasons. Despite his high-profile status and worldly mien, he’s small-town born and bred. He knows better than to put on airs. Red Brokaw saw to that. In A Long Way From Home, Brokaw shows no shame in listing the lessons he learned from his hardworking father and the bruising his ego took when he needed to be put in his place. It’s given him an equanimity that serves him well as a newcomer.

“When I first moved there, I was stopped on the streets of Livingston and Big Timber by every other cowboy saying, ‘I used to hunt on your property. Can I do it again?’ And I said, You know, I’m just going to have to say no to everyone until we sort this out.’ And then we hired an outfitter who had rights on there. And he came and said, ‘I’d like to put some hunters in.’ So we did a trade with him. I don’t think we ever got our end of the trade. That’s fine. And I said, ‘Sure, come on with your hunters.’ And then our manager hunts. And then we generally allow the guy who does our waste management stuff. He comes and picks up the trash once a week. And I think the UPS driver this year got to shoot a cow.

“As I often say to my friends, and I’ve got a lot of friends who lived in Montana all their lives, I say, ‘You know, when I first started coming to this area, I don’t remember the local ranchers standing out in the highway saying, ‘Come hunt on my land,’ or ‘Please come fish in my section of the stream. I’d love to have you over here.’ It didn’t happen that way,” he says.

Brokaw recognizes the responsibilities that come with owning land. “For the most part, most people are buying that land because of its beauty, and it speaks to them in a way. And certainly that’s our intention.”

Phrases like “getting biologicals” and “good for the ground” are the type of talk one typically doesn’t hear emanating from a corner office at Rockefeller Center. Maybe at Val’s Deli in Wilsall, Montana. Then again, this is Tom Brokaw speaking. Not the Tom Brokaw with 10 Emmys lining his office walls, but the one whose bison herd will put on more pounds because of the richer soil. The man has found a way to balance two wildly divergent lifestyles, and he’s done so in a manner that not only is rewarding for him and his family but also is a challenge.

“It’s a constant state of discovery I’d say about my two lives,” he says. “This is part of my life, and that’s part of my life. I get up every morning in New York City thinking something exciting is going to happen in this city today. This is just the nature of the city. I get up every morning in Montana saying, ‘I’m going to see something today I haven’t seen before.’”