In Koontz v. St. Johns River Water Management District, the high court finds it unconstitutional to use the permitting process as a tool of extortion.

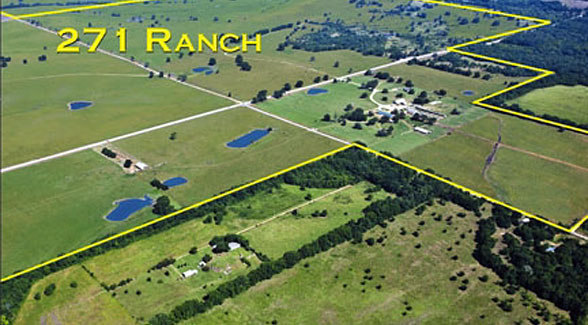

When Coy Koontz filed an application for a permit to develop 3.7 acres of a 14.9-acre parcel in 1994, he could hardly have imagined it was the beginning of a 20-year odyssey that would eventually wind its way to the U.S. Supreme Court. In 2000, long before the fight was over, the Central Florida developer passed away. He left his land and a titanic struggle to his son, Coy Koontz Jr.

On June 25, the Koontz family’s decades-long legal battle resulted in a 5-4 victory over the St. John’s Water Management District in what will be regarded as one of the most important property rights victories in a generation.

Koontz wanted to construct a commercial building on a portion of his property — a spot without any wetlands or sensitive habitat. The site Koontz selected was actually located on an existing street. As required by state law, Koontz offered to compensate for any wetland damage by deeding an 11-acre conservation easement. The district responded by threatening to deny a land-use permit unless Koontz either scaled back his project to a single acre and deeded an easement on the rest of his property or proceeded as planned and “mitigated” the alleged loss of non-existent wetlands by paying tens of thousands of dollars to maintain wetlands on another parcel miles away.

The water district made Coy Koontz an offer it thought he couldn’t refuse. Either scale back his 3.7-acre development to a single acre and turn over more than 11 acres to the state, or continue with his development and pay tens of thousands of dollars to “mitigate” the alleged loss of non-existent wetlands. Koontz refused both options. Instead he took the agency to court.

The ensuing case — Koontz v. St. Johns River Water Management District — goes to the heart of the Constitution’s Takings Clause: “nor shall private property be taken for public use, without just compensation.” For more than 25 years, the Supreme Court has deemed it unconstitutional for government entities to deny a building permit to a property owner simply because the owner refuses to hand over an unreasonable portion of his or her property to the public, free of charge, in exchange. In 1987, Nollan v. California Coastal Commission, the court struck down the agency’s policy of prohibiting property owners from rebuilding or expanding their homes unless they agreed to deed access to the beach in front of their home. A similar decision followed in 1994 when the court ruled in Dolan v. Tigard that it was impermissible for the City of Tigard to require a hardware store to give up a portion of its land for a bicycle path as a condition of getting a permit.

According to the Court, government agencies can impose conditions on building permits but those conditions must be “roughly proportional” to the public burdens of the proposed development. For instance, if a new building is going to increase vehicular traffic around it, a city could demand the owner give up a portion of its land to widen the street. But it is wrong, the Court continued, to make individual property owners pay for public benefits – like bike paths, public parks, or other public amenities – which in justice and fairness, should be borne by the public as a whole. Leveraging the permit process that way, the court famously said in Nollan, is “out and out extortion.”

Government agencies have been trying to skirt those decisions by arguing that although they limited how much land could be demanded of a property owner, they did not limit how much money could be required. This is why the St. John’s Water Management District told Coy Koontz that, in lieu of a smaller development, he could get the permit he sought by paying money. In the Koontz decision, however, the Court ruled it unconstitutional to use the permit process as a tool of extortion, whether the government demands cash or land.

Writing for the majority, Justice Samuel Alito wrote “land-use permit applicants are especially vulnerable to [this] type of coercion … because the government often has broad discretion to deny a permit that is worth far more than property it would like to take [a]nd can pressure an owner into voluntarily giving up property for which the Fifth Amendment would otherwise require just compensation.”

The water district did itself no favor by making a surprisingly technical argument to the Court. It took the position that it was not engaged in extortion because, unlike past cases, it did not tell the Koontz family that they would get a permit as soon as they handed over land or money. Instead, they told the family they would be denied a permit unless they handed over land or money. In a model of judicial engagement, the Court recognized this as a distinction without a difference, holding that it was still extortion and still unconstitutional.

In addition to reversing a Florida Supreme Court ruling, the Supreme Court remanded the case back to the Florida Supreme Court for further consideration and – the Koontz family hopes – a quick decision that leads them to finally get their building permit.

Larry Salzman is an attorney with the Institute for Justice. He wrote about Sackett v. EPA in our Summer 2012 issue. In Koontz, the Institute filed an amicus brief on behalf of itself and the Cato Institute in support of the Koontz family. For more information, visit www.ij.org.