Warning: Array to string conversion in /home/domains/dev.landreport.com/public/wp-content/plugins/elementor/core/dynamic-tags/manager.php on line 64

Warning: Undefined array key "separator_height" in /home/domains/dev.landreport.com/public/wp-content/plugins/jet-tricks/includes/addons/jet-unfold-widget.php on line 942

In her new book, Kathleen Shafer probes a Far West Texas phenomenon as improbable as the mysterious Marfa Lights.

Text by Kelly McGee | Photography by Gustav Schmiege III

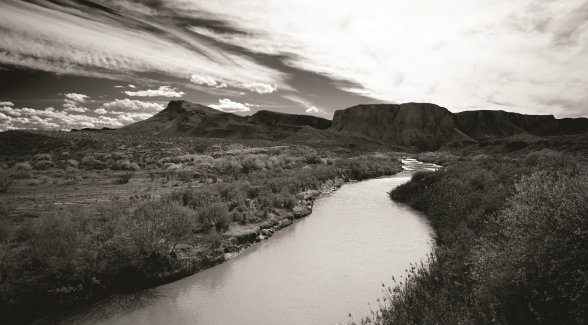

Marfa is more than a trendy town. It has morphed from a pokey county seat into a global brand. Some see it as an art mecca. Others as an international intersection. Think “Last Best Place.” This aura has only been enhanced by the movies and TV shows shot there.

Yet none of these descriptions accurately convey the coming of age of this small town with the big vistas. Give Kathleen Shafer credit for dissecting Marfa’s rise from the ashes and sharing with readers a cogent explanation of how and why Marfa came to be what it is today.

For more than a century, Marfa was the thriving capital of a cattle kingdom that spanned hundreds of thousands of acres of Far West Texas. But the gradual fragmentation of the great ranches took its toll, and by the early 1970s, the local economy was on life support.

Enter Donald Judd (1928—1994). While Marfa was ailing, Judd was chafing. The renowned minimalist artist found New York’s gallery scene too confining for his oversized creations. So he set out in search of much bigger spaces. Wide-open spaces. Some 20 miles west of Alpine, he found them everywhere he looked.

Marfa’s desolate landscape became Judd’s ultimate canvas. Its many empty buildings became studios for his works and the works of artists whom he admired such as Dan Flavin and John Chamberlain. Odd though it may seem, by seeking to escape to nowhere, Judd and his artwork actually created somewhere.

Some locals were definitely put off by the arrival of Judd and Co. More than likely, however, they resented the fact that he snapped up much of downtown (16 buildings) and purchased a local landmark, the old Army base, Fort D.A. Russell.

Some locals were definitely put off by the arrival of Judd and Co. More than likely, however, they resented the fact that he snapped up much of downtown (16 buildings) and purchased a local landmark, the old Army base, Fort D.A. Russell.

But the truth is the locals had little choice but to embrace or at least tolerate Judd. The economic impact of his artistic enterprise was the only thing keeping the town alive.

Judd’s zeitgeist did, however, appeal to outsiders like Tim Crowley, a Houston litigator who moved to Marfa in 1997. Two decades later, Crowley opened the 55-room Hotel St. George. His chic hotel is one of hundreds of investments by out-of-towners that have bolstered local tax rolls and expanded the tourism trade.

As one Marfa resident put it, “Crowley gave us a place to be cool. He gave us a place to hang out. He brought his rich friends. He invested money.” Success breeds success, which is why films such as No Country for Old Men and There Will Be Blood led to TV shows like I Love Dick. Marfa is now an experience that visitors can enjoy as they choose, be it as a hipster, an urban refugee, or an artist on a mission.

RELATED ARTICLES

FOR SALE: Little Woody Creek Ranch

John and Aimee Oates bid a fond farewell to their Aspen getaway. Text by Eddie …

Midwest Farmland Values Up In the Third Quarter

The overall 2 percent rise represents the first year-over-year increase in ag land values in …

Ag Exports Feed World Demand

Speaking of breaking records, this year could set a new level for American ag exports. …

Elk Creek Ranch Acquires Seven Lakes

For those who are passionate about outdoor pursuits, the next great adventure can’t come soon enough.