Landowners, Ranchland, Sporting Properties

- September 8, 2019

-

Views: 126

Travelin’ Man

Warning: Undefined array key "separator_height" in /home/domains/dev.landreport.com/public/wp-content/plugins/jet-tricks/includes/addons/jet-unfold-widget.php on line 942

Don’t tell T.D. Kelsey what he can or can’t do. Somehow, some way, he does it all, he does it well, and he does it his way.

By Henry Chappell

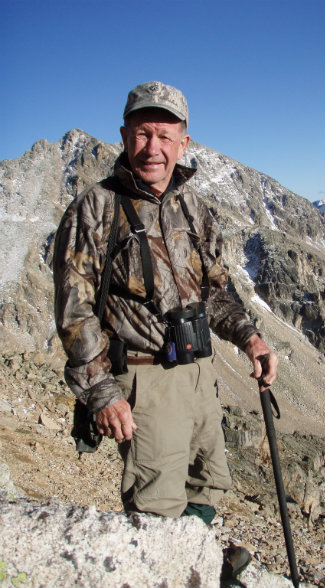

Photography by Wyman Meinzer

Near the end of his life, George Phippen (1915–1966) recognized a great mistake. One of the founders of the Cowboy Artists of America, the renowned sculptor spent the latter part of his life sculpting and ranching in Skull Valley, Arizona. By the time he realized he should have focused solely on his art, it was too late.

“Don’t you make the same mistake,” Phippen’s widow told a 23-year-old aspiring sculptor named T.D. Kelsey. The year was 1969, and T.D. was about to have his first sculpture cast. He politely listened and promptly ignored Louise Phippen’s advice. The sculptor has been ranching ever since.

It’s a revealing anecdote, one that illustrates much about this fascinating character. No one ever taught T.D. how to sculpt. The plain-spoken cowboy just picked up some clay and started sculpting. Piloting a plane? His professional career can be traced to a morning’s lessons in a Piper J-5. (P.S. This lack of formal training did not prevent United Airlines from hiring him to fly DC-6s and 727s. More about this episode later.) In that rarest of genres — the self-made man — the diminutive cowboy stands head and shoulders above all comers.

“I’ve never met anyone like him,” says Herbert Allen of Allen & Company. “Everything T.D. touches he does at a world-class level. He’s an accomplished artist, a self-taught pilot, and a world-class hunter.”

This self-reliance is on full display the morning The Land Report arrives at his West Texas ranch. A norther had pummeled the Rolling Plains, and power was out at the T Lazy S Ranch. For that matter, so was cell phone service. Not to worry. An oversized enamel coffee pot, the big blue kind found in most chuck wagons, sat burping in the fireplace.

“I drink 10 or 12 cups a day,” T.D. says. “We weren’t about to do without coffee.” Short, with a trim, athletic build perfect for the saddle or the cockpit of an old crop duster, he points to the mounted big game heads that cover the walls.

“I’ve never been a trophy hunter. I shot most of these for camp meat,” he says. His soft, quick speech isn’t quite Texan. It comes across more like that of a Wyoming cowboy.

I was close. Terry Duen Kelsey was born in 1946 in the town of Shelley in Southeastern Idaho. His father, Duen Kelsey, piloted a P-51 Mustang during World War II. After V-E Day, he continued to fly as a crop duster and established an airfield in Blackfoot, which became his base. T.D.’s mother, Jean, stayed home and raised him, his sister, Susan, and their three brothers.

In 1950, the Kelseys left Idaho for Montana. At first, they rented a place on the edge of Bozeman. Soon afterward, they moved 20 miles north to a small ranch next to a national forest. A 55-gallon drum fashioned into a wood stove heated the dirt-floored log cabin. The kids slept in one room; the parents in the other. Running water came from a creek, and when nature called, the outhouse was a short, often chilly walk.

In an unpublished memoir, T.D.’s younger brother Mike described those early days: “[T.D.] was Dad’s shadow. They fished, hunted, and broke horses together. Terry rode saddle bronc in rodeos, wrestled, and loved to draw when he was young.”

In 1962, Duen Kelsey was helping a neighbor when an augur shorted and electrocuted him. He did not survive. Shortly afterward, one of T.D.’s uncles called. He owned a crop-dusting business and asked the teenager if he “planned to be a fly boy” like his dad. “He found an old Piper J-5 in Soda Springs, Idaho, and I traded three rifles for it,” T.D. recalls.

“We went there, pumped up the tires, drained the oil out, warmed it up, and put it back in so we could get it started. He flew me around Soda Springs a few times, and we did three or four landings. Then he said, ‘You’re good. I’ll see you in Blackfoot.’ I flew back following the highway and was shaking the entire time. It took me five passes before I finally got it on the ground. A couple days later, I flew to Montana. There weren’t a lot of people to show me how to do other things. Everybody was busy working.”

Between buzzing crops and breaking horses, the teenager sketched and studied. “I drew a lot — sketching first. I didn’t sculpt until I was 18, and then only a couple stone carvings,” T.D. says. His early inspirations? “Russell and Remington, of course, but Russell seemed unapproachable, so far up there. I really studied Will James. He was more down to earth, and his books were easy to find. My mother would tell me to quit walking around bow-legged, trying to be Will James,” he says with a laugh.

A cutting horse trader named Ned Johnson moved to Bozeman in 1962. His daughter, a tenth-grader like T.D., caught the young pilot’s eye.

“I fell madly in love with Sidni the minute I saw her, but she wouldn’t have a thing to do with me because I was pretty rowdy in high school,” he says.

After helping her with her chemistry for what must have seemed like ages, he finally talked her into going out on a date. They registered their T Lazy S brand before graduating from Bozeman Senior High and got married that very fall.

Crop dusting and shoeing horses didn’t exactly put the young couple in high cotton, especially since T.D. was also enrolled at Montana State College.

In 1967, Sidni’s sister, a flight attendant, learned that a recruiter from United Airlines was coming to Bozeman. It was the height of the Vietnam War, and the manpower requirements of the different branches of the armed forces had caused a serious shortage of commercial pilots. T.D. had considered pursuing a career as a military pilot but hadn’t finished college. “I didn’t think I could be a pilot because I didn’t have a degree. Fortunately, the airlines were desperate,” he says.

After impressing the recruiter, T.D. drove down to Blackfoot to take a test at the airfield his father had established. Afterward, United sent him to Seattle to take a Stanine test.

Says T.D., “It sounded like a physical fitness test, so I worked like hell to get into shape. But it turned out to be a test of spatial ability. I must’ve passed because they said, ‘Come on.’”

But he couldn’t, not just yet. He wasn’t 21. Finally, many moons after his uncle first taught him to fly, T.D. enrolled in flight school. He checked out in a DC-6. His first route was San Francisco to Sacramento, Ely, Elko, Salt Lake City, and Reno. “We didn’t night over anywhere,” he says. “Those were long days.”

His workday didn’t get any shorter when he moved up to 727s in 1969. He wanted to quit flying and become a full-time rancher and artist, but United convinced him to take a leave of absence. He and Sidni were on track to buy a ranch in North Dakota, but title issues nixed the deal. They ended up buying a ranch in Kiowa outside of Denver. He ranched during the day and flew 727s out of Denver’s Stapleton Airport at night.

One day, T.D. invited a United pilot named Ted Gobel to stop by his Kiowa ranch. Gobel happened to be a nephew of the legendary artist George Phippen, and during his visit, he remarked that his Aunt Louise would soon be visiting Denver and would love to see his work. Louise Phippen not only came to the ranch, but she insisted that T.D. sculpt a piece for her son to cast at his foundry.

“You do something,” she commanded.

For once, T.D. did as he was told.

“I ended up doing a sculpture of a guy snubbing a horse and took it down to Prescott, Arizona. Ernie Phippen cast it in red bronze. We did it the old way. We put the wax in it, put the pins in it, poured a core, built an oven around it, burned the wax away, tore the oven down, shored up the shell, built up the oven again, and then poured the bronze in,” he says.

Ernie Phippen also cast T.D.’s next two pieces — a cowboy throwing a loop known as the Johnny Blocker, and a bucking horse. “Horses, of course. Always horses in those days,” T.D. says.

That first piece, called Rough String Makings, ended up going to the East Coast. A Western Horseman profile on T.D. caught the attention of a Brooklyn-based collector, and it immediately sold.

Throughout the 1970s, Sidni encouraged T.D. to draw, paint, and sculpt, as he continued to ranch and fly for United. In 1971, he and his partner and ranching mentor, Minford Beard, under a contract with Uncle Sam, began chasing and catching wild horses in the rough country along the Colorado-Utah border and selling them to eager buyers. Every winter for 25 years, the two men caught yearlings to control herd population and rotated studs to minimize inbreeding. “I was obsessed with wild horses,” T.D. says. “So much so that I probably wasn’t very pleasant to be around.”

Despite a full-time job as a pilot and obsessions with ranching and wild horses, he continued to develop as an artist and produce works for a growing number of collectors.

At Sidni’s urging, T.D. quit flying in 1979. “United Airlines was so good to me, but I grew bored. The day came when I realized that I got a lot more excited walking into my studio than sitting down in the cockpit of a 727,” he said.

It took a few years for the momentum to build, but in 1985, T.D.’s career as an artist took off. The catalyst was a donation that Sidni and he made to the City of Fort Worth. Cast in 900 sections, Texas Gold is a monumental sculpture of longhorn cattle that has welcomed millions of visitors to the Fort Worth Stockyards in the decades since.

That very same year, T.D.’s brutal workload caught up with him; he suffered a severe heart attack that almost took his life. Angioplasty saved him. Sidni insisted that he work less and have more fun. As soon as he returned to fighting form, T.D. loaded up a backpack and trekked into the woods where he rediscovered his love of hunting.

“When I was a young man, I started noticing trash left by hunters in the backcountry. It disgusted me so that I turned away from hunting for the better part of two decades. Those backpacking trips revived my interest in hunting, hiking, and wildlife. I’ve made several trips above 15,000 feet with no problems.”

T.D.’s new lease on life also led to an increased interest in wildlife sculpture. Monumental works like Swamp Donkey, which was purchased by Tom and Meredith Brokaw, and Testing the Air, which was acquired by The National Museum of Wildlife Art, joined bronzes of mustangs, cowboys, and longhorns.

With Sidni’s encouragement, trips to Africa soon followed. “I’ve always read every book on Africa I could get my hands on. Sidni insisted I borrow the money and go,” he says. What started as a four-day trip to Zimbabwe turned into a 30-year love affair with Africa.

“My guide and I became great friends. He got me to a phone, and I called Sidni and said, ‘Get over here!’ She flew over, and on the way to get her, our Range Rover broke down. We were five hours late picking her up at the tiny bush airport. I was worried to death, but there she was, sitting beneath a tree, waiting for us. She fell in love with Africa. We made every trip together from then on.”

T.D. studied African elephants in their native habitat for 27 years before sculpting His Team, which features an old bull elephant alongside two younger, subordinate males. His many trips to the Congo, Ethiopia, Mozambique, South Africa, Uganda, Zambia, and Zimbabwe inspired dozens of works featuring Cape buffaloes, kudus, lions, sables, warthogs, and other African game.

In 1989, Tulsa’s Gilcrease Museum honored T.D. as its Rendezvous Sculptor of the Year. A one-man exhibition followed. He was now a true force in contemporary Western sculpture. In the 1990s, T.D. met Herbert Allen Jr. at the Will Rogers Arena in Fort Worth. The president of Allen & Company and the Western artist became fast friends as well as globetrotting cycling partners. Allen himself and Allen & Company have since become the largest collectors of T.D.’s sculptures.

“I’m no artist, but I know what I like. I immediately found T.D.’s work appealing,” Allen says.

Throughout the late 1980s and early 1990s, T.D.’s work grew more impressionistic. “Looser” is the term he uses. The initial change began one day when he walked into his Colorado studio and began to work obsessively. Sidni came in to bring him food and coffee.

“When I came out of there, I had a finished sculpture,” he says. “A pickup rider, and another guy, both on emaciated horses. Very loose, unlike anything I had done before. Sidni asked, ‘Do you know what day this is?’ I hadn’t thought about it, but it was the anniversary of my father’s death. And I was the same age as he was when he died.”

Some of his collectors were dismayed by the stylistic change, but T.D. stuck to his guns. The piece went unsold for more than a year. It eventually sold, and then the entire edition got snapped up in a couple of months. “I’ve been trying to be more impressionistic ever since. When I safety up because of a tight deadline, my work gets tighter, more detailed, and I don’t get those butterflies in my stomach like I do when I walk into the studio to start a looser work,” he says.

In 1994, the Kelseys traded their Colorado ranch for 8,000 acres in the pine ridge country just outside Billings, Montana. Much to T.D.’s horror, his wife soon developed cancer. In 2000, his high school sweetheart succumbed to the disease. Always T.D.’s biggest supporter, Sidni kept the original of every one of his sculptures. Given her love of Cody and the Kelseys’ strong relationship with Byron Price, T.D. selected the Buffalo Bill Center of the West to house the 166-piece Sidni Kelsey Collection.

“This comprises one of the strongest collections, if not the strongest, outside of T.D.’s own collection,” says Karen McWhorter at the Center’s Whitney Western Art Museum.

“I love that T.D. adds artfulness as well as authenticity to his subjects. I really appreciate the surface area of his sculptures. You can really see his hands. Everyone wants to touch the surface of his monumental works even though we’d rather they didn’t. They’re that magnetic,” McWhorter says.

Several aspects of T.D.’s style stand out to Price, who has since moved on from the Buffalo Bill Center and is now the director of the University of Oklahoma’s Charles M. Russell Center for the Study of Art in the American West:

“T.D. has such an authentic approach and feel and sentiment for the West that’s imbued in his work. My favorite characteristic is his ability to infuse motion into his sculptures — a skill that took Fredrick Remington a long time to develop. T.D. can make that metal move in ways that others don’t. He has a little bit of Charlie Russell in him in that his relationship to the animals is sympathetic. He has that ability to evoke character in animals as well as people.”

Ultimately, remaining in Montana was not an option for the heartbroken cowboy. “It was such a gorgeous ranch, and we had such plans for it, but it was just too sad without Sidni.”

A few years after her death, he sold the property and set his sights on a new beginning. He turned to a fellow Colorado rancher – John Welch – for advice. Welch enjoyed one other distinction.

As the Spade Ranches CEO, Welch was well acquainted with the differences between landowner rights in Texas and those out West. This was a top priority for T.D., who all too often encountered trespassing hunters who considered his private property their public land. Welch recommended he take a closer look at Texas’s Rolling Plains and introduced him to Sam Middleton. The third generation CEO of his family’s brokerage, Middleton ranks as one of the state’s most trusted brokers, which is why he’s also one of its most successful. After listening to T.D. describe some of the brazen trespassing that he had endured, Middleton told him, “Us folks here in Texas don’t think like that.”

At the time, a rough portion of the Four Sixes country was on the market. T.D. made an offer and made it his own.

Says Kelsey, “I’ve just always felt that I need to be a rancher because I’m a cowboy artist. Every time you go out, there’s a million ideas waiting for you. I don’t have the means to ranch on the scale of the Four Sixes or the Pitchfork, but I think it’s really important that artists don’t lose that iconic image of the cowboy that’s unique to the United States.”

T.D. runs calves on the T Lazy S when conditions allow. He also keeps a few exotics for study purposes. Thanks to his steady output, he continues to attract new admirers. Many of his most ardent collectors are ranchers. Art Nicholas is a global investor who ranked No. 75 on the 2018 Land Report 100. He placed T.D.’s sculptures at his Wagonhound Ranch in Wyoming as well as at the corporate headquarters of Nicholas Investment Partners in San Diego.

“T.D.’s work is spontaneous and authentic because he really knows his subject matter. As a collector, I really like the fact that he does low edition numbers,” Nicholas says.

During our visit, T.D. shows us around a small studio packed with skins, skulls, spears, bows, and poison-tipped arrows, along with photos from Africa, Australia, Mongolia, and other wild places. In a larger studio, a towering rendition of Icarus awaits the maestro’s final touch. Near the sculpture stands a Piper Pawnee, a sprayer from T.D.’s crop dusting days. There’s also a Robinson R44. That would be a helicopter.

“You fly helicopters?” I ask.

“I do. Bought an R22 from a guy in the Panhandle three years ago. A year later, I was in the Yukon and heard about an R44 an a farm sale. Sent a bid down and got it. I was lucky. It was airworthy. ”

Another metal-sided building hangars a Yakovlev Yak-9 and a Super Pitts S1T. The Russian Yak was the workhorse of the Soviet air force. During World War II, it turned the tide against the Luftwaffe. The Super Pitts is a beast, one of the most successful competition aircraft in history. With another 10,000 acres to explore on T.D.’s ranch, there’s no telling what other inspirations he’s got tucked away in its nooks and crannies.

History, in all its fickleness, will be the final judge of T.D. Kelsey’s oeuvre. In the meantime, there’s no denying that the quiet cowboy proved Louise Phippen wrong. Given immense talent, a loving partner, limitless curiosity, and way too much coffee, it is actually possible to be a sculptor and a rancher.

Warning: Undefined array key 0 in /home/domains/dev.landreport.com/public/wp-content/plugins/elementor-pro/modules/dynamic-tags/acf/tags/acf-url.php on line 34

Warning: Undefined array key 1 in /home/domains/dev.landreport.com/public/wp-content/plugins/elementor-pro/modules/dynamic-tags/acf/tags/acf-url.php on line 34

RELATED ARTICLES

The Land Report Looks at Barack Obama

After analyzing George Bush’s legacy with respect to landowners, scrutinizing the inclinations of lawmakers in …

The Land Report Spring 2014

2013 was a year of superlatives: billion-dollar acquisitions, record-setting prices, and landmark sales. And behind …

Tom Brokaw’s West Boulder Ranch Sells; Burnt Leather Ranch Included in Transaction

Combination of adjacent Montana listings creates peerless 4,751-acre property with world-class recreational features. Tom Brokaw’s …

Elk Creek Ranch Acquires Seven Lakes

For those who are passionate about outdoor pursuits, the next great adventure can’t come soon enough.